Story Info

Story Info

Cynthia Keyworth

Tucson, AZ

2011

Type of Wounded Place

Story & Experience

I was fortunate to grow up in Tucson in the 1950s, a world where there were many opportunities to be in nature—vast tracts of empty desert, uninhabited foothills and mountain ranges. My family had favorite spots for picnicking at Gate’s Pass, in cattle country south of town, on Mt Lemmon, and in Sabino Canyon, and we rarely had to share these places. The population of Tucson in 1950 was 45,000: There was plenty of silence and space for anyone who wanted it.

In the fifties and sixties, however, Tucson experienced explosive population growth as people moved west for the climate, jobs, cheaper housing, the magic of the West, and the lure of wide open spaces. The town boomed and sprawled. For politicians and city planners, the idea of planned growth was an oxymoron. Why restrain prosperity?

Today, metropolitan Tucson is closing in on one million inhabitants, and the desert valley continues to be relentlessly converted into housing developments, shopping centers, streets and roads, fire houses, malls, schools, multiplexes, and gas stations. New houses appear, almost overnight it seems, on the flanks of the foothills, inching up into genuine mountain terrain.

I find these changes hard to accept. When I see more houses going up (and notice the flimsy wallboard-and-staple-gun construction), I can hardly bear to look. And every time I turn my head to avoid the sight of a new “Hi honey I’m home, Hi honey I’m home, Hi honey I’m home” development, my heart tightens and I think about how denial damages the soul.

So I decided that on June 18, I would begin some process of acceptance. The place I chose for this exercise was Sanctuary Cove, eighty acres of mountain and bajada west of Tucson, private land that is open to the public. Years ago, I often went there to go hiking and bird watching until the sight of house after house polluting the view depressed me too much. Today, I wanted to hike up to some height in the red-rock bajada and contemplate that wounded view.

Then, as I was driving north this morning on Silverbell (a winding road that used to be in the backcountry), a question—and answer—occurred to me. Who is wounded: you or the view? The answer came: I am. I want the wide empty spaces of my childhood restored. I want wilderness areas as they were in the fifties. I do not want what is. I am arguing with reality.

Those who live in the developments I detest—some houses plain and sad in their sameness, some ugly and expensive, some nice with trees and plantings—do not think of their homes as mutilations on the face of nature. They were not here sixty years ago when this land was wild with coyotes and snakes and mountain lions; they weren’t here twenty years ago—or even five. They are glad to get up in the morning and see the mountains nearby and hear desert birds singing (except when they have to deal with coyotes and snakes). They are mothers and fathers pushing baby strollers, older women walking, kids on bicycles, couples running. I drove through some of these areas this morning and felt empathy for their desire to live here. The dwellers in the sprawl are not to blame for the sprawl itself.

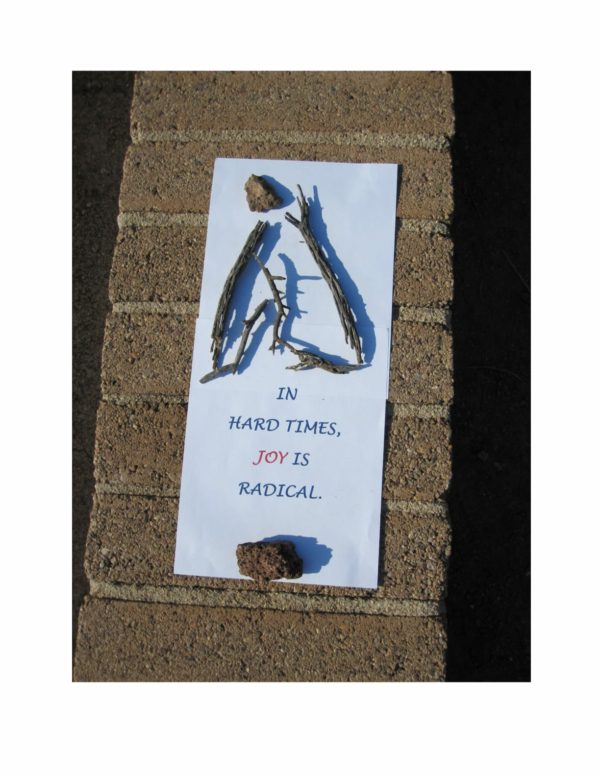

When I got to the Cove, I turned my back on the valley and revelled in nature—accompanied by the distant sound of the traffic. This small mountain range stands in the litter of itself—red volcanic rock. Cactus wrens sing. A few saguaros still have their creamy white blossoms. Lizards skitter. Breezes lull and regroup. Cool shade can be found west of any palo verde tree. I decided it was too hot and I was too old to make the climb up to the saddle beneath Safford Peak, as I had planned to do. Instead, I hung around a small chapel on the property. Behind it is a kind of podium made of rocks and an “amphitheater”—rows of brick benches—and on the back row I made a simple assembly of a few sticks and a rock to create a (very abstract!) bird. A wedding was going to take place there later, and for a while I listened to a gentleman practicing the bagpipes as I sat on one of the long benches, looking at the dust hanging over the valley. The raw developments I had disliked had been softened over time with trees and other plantings. Above us all, the sky was wide, blue, and empty; the air was hot and dry. It was incredibly beautiful there. The small spare “piece of beauty” I made was not to heal the valley but myself, and to celebrate the sanctuaries of nature that are still available to me. My only ceremony was to sit quietly. I was brought to remember that Nature doesn’t only mean wild remoteness or rain forests; it’s also a scrubby mountainside within sight of civilization that still nurtures coyotes, snakes, ground squirrels, lizards, birds, mountain lions, saguaros, rattlesnake weed, the human soul. I felt peaceful in that thought.

But I left the Cove unsettled by too many questions. How can city planners be encouraged to build wisely and to consider community, energy needs, transportation requirements, land conservation, and the beauty of our landscape? What happens as we continue lose natural spaces to over-development? How can I help support conservation of natural areas? What do I—offer money or time? What could be the role of a sixty-eight year old poet who doesn’t have a lot of either commodity?

Driving back on Silverbell, I stopped at a small plant nursery that’s been in business for twenty-five or thirty years—a lifetime in this town. It hadn’t opened its doors yet, but I was glad to see that the place looked well-stocked and thriving. I suspect the many new residents in the area have contributed to its success.

I was fortunate to grow up in Tucson in the 1950s, a world where there were many opportunities to be in nature—vast tracts of empty desert, uninhabited foothills and mountain ranges. My family had favorite spots for picnicking at Gate’s Pass, in cattle country south of town, on Mt Lemmon, and in Sabino Canyon, and we rarely had to share these places. The population of Tucson in 1950 was 45,000: There was plenty of silence and space for anyone who wanted it.

In the fifties and sixties, however, Tucson experienced explosive population growth as people moved west for the climate, jobs, cheaper housing, the magic of the West, and the lure of wide open spaces. The town boomed and sprawled. For politicians and city planners, the idea of planned growth was an oxymoron. Why restrain prosperity?

Today, metropolitan Tucson is closing in on one million inhabitants, and the desert valley continues to be relentlessly converted into housing developments, shopping centers, streets and roads, fire houses, malls, schools, multiplexes, and gas stations. New houses appear, almost overnight it seems, on the flanks of the foothills, inching up into genuine mountain terrain.

I find these changes hard to accept. When I see more houses going up (and notice the flimsy wallboard-and-staple-gun construction), I can hardly bear to look. And every time I turn my head to avoid the sight of a new “Hi honey I’m home, Hi honey I’m home, Hi honey I’m home” development, my heart tightens and I think about how denial damages the soul.

So I decided that on June 18, I would begin some process of acceptance. The place I chose for this exercise was Sanctuary Cove, eighty acres of mountain and bajada west of Tucson, private land that is open to the public. Years ago, I often went there to go hiking and bird watching until the sight of house after house polluting the view depressed me too much. Today, I wanted to hike up to some height in the red-rock bajada and contemplate that wounded view.

Then, as I was driving north this morning on Silverbell (a winding road that used to be in the backcountry), a question—and answer—occurred to me. Who is wounded: you or the view? The answer came: I am. I want the wide empty spaces of my childhood restored. I want wilderness areas as they were in the fifties. I do not want what is. I am arguing with reality.

Those who live in the developments I detest—some houses plain and sad in their sameness, some ugly and expensive, some nice with trees and plantings—do not think of their homes as mutilations on the face of nature. They were not here sixty years ago when this land was wild with coyotes and snakes and mountain lions; they weren’t here twenty years ago—or even five. They are glad to get up in the morning and see the mountains nearby and hear desert birds singing (except when they have to deal with coyotes and snakes). They are mothers and fathers pushing baby strollers, older women walking, kids on bicycles, couples running. I drove through some of these areas this morning and felt empathy for their desire to live here. The dwellers in the sprawl are not to blame for the sprawl itself.

When I got to the Cove, I turned my back on the valley and revelled in nature—accompanied by the distant sound of the traffic. This small mountain range stands in the litter of itself—red volcanic rock. Cactus wrens sing. A few saguaros still have their creamy white blossoms. Lizards skitter. Breezes lull and regroup. Cool shade can be found west of any palo verde tree. I decided it was too hot and I was too old to make the climb up to the saddle beneath Safford Peak, as I had planned to do. Instead, I hung around a small chapel on the property. Behind it is a kind of podium made of rocks and an “amphitheater”—rows of brick benches—and on the back row I made a simple assembly of a few sticks and a rock to create a (very abstract!) bird. A wedding was going to take place there later, and for a while I listened to a gentleman practicing the bagpipes as I sat on one of the long benches, looking at the dust hanging over the valley. The raw developments I had disliked had been softened over time with trees and other plantings. Above us all, the sky was wide, blue, and empty; the air was hot and dry. It was incredibly beautiful there. The small spare “piece of beauty” I made was not to heal the valley but myself, and to celebrate the sanctuaries of nature that are still available to me. My only ceremony was to sit quietly. I was brought to remember that Nature doesn’t only mean wild remoteness or rain forests; it’s also a scrubby mountainside within sight of civilization that still nurtures coyotes, snakes, ground squirrels, lizards, birds, mountain lions, saguaros, rattlesnake weed, the human soul. I felt peaceful in that thought.

But I left the Cove unsettled by too many questions. How can city planners be encouraged to build wisely and to consider community, energy needs, transportation requirements, land conservation, and the beauty of our landscape? What happens as we continue lose natural spaces to over-development? How can I help support conservation of natural areas? What do I—offer money or time? What could be the role of a sixty-eight year old poet who doesn’t have a lot of either commodity?

Driving back on Silverbell, I stopped at a small plant nursery that’s been in business for twenty-five or thirty years—a lifetime in this town. It hadn’t opened its doors yet, but I was glad to see that the place looked well-stocked and thriving. I suspect the many new residents in the area have contributed to its success.

Tucson, AZ

Image Credit:

- Keyworth: Cynthia Keyworth

RECENT STORIES

Remembrance Day for Lost Species in Helsinki 2023

On November 30th, there was first a session organized by the Finnish social and health sector project about eco-anxiety and eco-emotions (www.ymparistoahdistus.fi). This “morning coffee roundtable”, a hybrid event, focused this time on ecological grief [...]

Ashdown Forest

Ashdown Forest is an area of natural beauty in West Sussex, England. It is also one of the very few remaining areas of extensive lowland heath left in Europe. This rare and threatened landscape is [...]