Story Info

Story Info

James Mahoney

San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area

2010

Type of Wounded Place

Story & Experience

The San Pedro River in southeastern Arizona is the last undammed river in the state. Within the riparian corridor, largely limited to a 50 miles reach contained within the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, administered by the U. S. Bureau of Land Management, is the last largest and one of the rarest original forest types in North America, the: Fremont Cottonwood—Goodding Willow gallery forest.

A phenomenal diversity of migratory and resident avian species—over 400—are drawn to the corridor for its shelter and food supply. Over 80 species of mammals also pass through or reside in this ribbon of green in a sea of arid grasslands and desert. Superlatives abound in the corridor of the San Pedro River.

The evidence of mammoth hunters, 13,000 years old, continue to emerge from the upland soils. Native peoples called the San Pedro home throughout the millennia. Spanish occupation is evidenced with the remains of an adobe presidio built along a lonely stretch of the river in 1776. The Apaches forced the outsiders to withdraw after five violent years. Cattle ranching eventually came into the lush bottomlands. Railroads followed silver mining. People followed the railroads. But the river continued to flow, to provide for newcomers and old-timers, human or otherwise…until the 1970’s.

The expansion of the mission of the U. S. Army’s Fort Huachuca from keeping tabs on the Apaches, changed to keeping tabs on everything! The fort is the Army’s center for Intelligence and communication. This expanded role caused the sparse surrounding towns to sprawl. The population of the upper San Pedro River valley grew from 10,000 to 75,000 in less than 25 years. Municipal wells and private wells drilled by wildcat developers for the benefit of the burgeoning population is causing the ancient river to dry up. Simply put, a cone of depression at the top layers of the aquifer is pulling surface water away and far below the ability of the vegetation to quench and replenish.

The San Pedro River is the only dependable source of wild water for a distance of 300 miles to the east—the Rio Grande and 300 miles to the west—the lower Colorado River. Without the perennial flow of the San Pedro River, the old native forests and grasslands are desiccating and dying. As the vegetative habitat withers, the animal life—from the leopard frog and longfin dace to the gray hawk and green kingfisher to the nectar bats and ghosty neotropical cats, are essentially homeless and their cupboard is bare.

The legal battle to establish water rights for the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area is essential. But the adjudication is mired by lawyers, at the behest of politicians and developers, who scrutinize and protest literally every sentence, every table and graph, every piece of evidence that the BLM has collected and presented, establishing the numbers which equate to acre-feet of flowing water, vital for the survival of what The Nature Conservancy has called, “One of the last great places on Earth.”

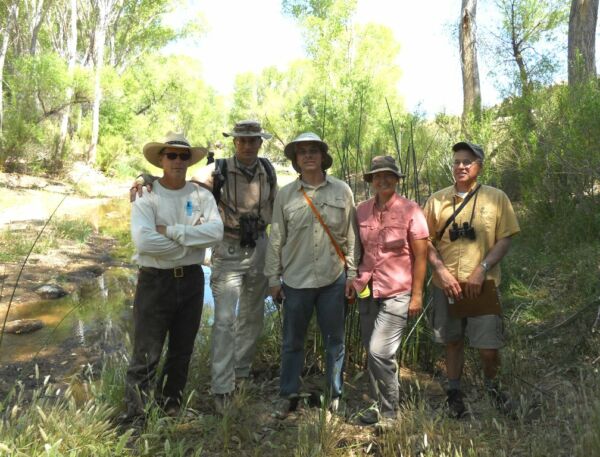

For twelve years, BLM employees and volunteers have walked the entire stretch of the river within the National Conservation Area at the time of the summer solstice—pagan celebration? Not quite. This is the driest time of the year. No matter how much monsoon rain fell the summer before or snowmelt from that winter, this is the time of year when the river and riparian habitat and most stressed. Eight teams of two to six folks—one team at the north end, the longest and driest, of four horseback riders—walk the river bottom with GPS units and notebooks in hand mapping the wet and dry lengths of the San Pedro River. For the past two years similar mapping has been carried out by partners in the rivers’ headwaters in Sonora, Mexico.

The data collected regarding animal sightings and the health of native habitat, notations regarding the intrusion of exotic species, the impacts of human visitation—legal or otherwise—and most especially the extant and changes over time to the perennial reaches of water have contributed to the body of science that is being used to save the river.

This year was different in one very important way. For the first time BLM’ers and volunteers were asked to record their deeper observations as they walked the San Pedro. The teams were asked to spend time during the day—in the SHADE!—quietly sitting alone or with their friends and colleagues, reflecting upon and if they desired, sharing their more personal, emotional, even spiritual, impressions of their relationship to the San Pedro River.

If they were old-timers to the place, they were asked to relate their first impressions of the river. If this was their first time in the area, they were asked to do the same. Comparisons and anecdotes abounded. They were asked to think about and if called to, discuss what they felt about the work they were doing mapping the river, about how they felt about the current situation as the water flows and habitat of the San Pedro River continues to decline in volume and health. They were asked if they had hope. Naturally, as most of the BLM employees and volunteers are or were professional scientists, talking about intangibles was difficult for some, even irrelevant. But others opened up and proved poignant and eloquent in their thoughts and speech—some surprising even themselves with the passion with which they spoke. Anger at the overt perpetrators was outed and covert actions proposed and then let go. Deep sadness was expressed. Guilt at being a human being and a contributor to the demise of an entire ecosystem was quietly born by the honest.

Yet, for all the somber reality of hiking a great simple river during her driest days, joy and refreshment and wonder at the rare beauty of this desert river were the largess of the day. For these human beings who have not given up hope, but continue to explore the San Pedro River and document, even if only in their hearts, what they see and smell, and hear and touch, and FEEL, was time very well spent. They will be there next year. They will be there for as long as they are needed. Until the San Pedro River flows with continuous wild abandon, as a river should.

The San Pedro River in southeastern Arizona is the last undammed river in the state. Within the riparian corridor, largely limited to a 50 miles reach contained within the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, administered by the U. S. Bureau of Land Management, is the last largest and one of the rarest original forest types in North America, the: Fremont Cottonwood—Goodding Willow gallery forest.

A phenomenal diversity of migratory and resident avian species—over 400—are drawn to the corridor for its shelter and food supply. Over 80 species of mammals also pass through or reside in this ribbon of green in a sea of arid grasslands and desert. Superlatives abound in the corridor of the San Pedro River.

The evidence of mammoth hunters, 13,000 years old, continue to emerge from the upland soils. Native peoples called the San Pedro home throughout the millennia. Spanish occupation is evidenced with the remains of an adobe presidio built along a lonely stretch of the river in 1776. The Apaches forced the outsiders to withdraw after five violent years. Cattle ranching eventually came into the lush bottomlands. Railroads followed silver mining. People followed the railroads. But the river continued to flow, to provide for newcomers and old-timers, human or otherwise…until the 1970’s.

The expansion of the mission of the U. S. Army’s Fort Huachuca from keeping tabs on the Apaches, changed to keeping tabs on everything! The fort is the Army’s center for Intelligence and communication. This expanded role caused the sparse surrounding towns to sprawl. The population of the upper San Pedro River valley grew from 10,000 to 75,000 in less than 25 years. Municipal wells and private wells drilled by wildcat developers for the benefit of the burgeoning population is causing the ancient river to dry up. Simply put, a cone of depression at the top layers of the aquifer is pulling surface water away and far below the ability of the vegetation to quench and replenish.

The San Pedro River is the only dependable source of wild water for a distance of 300 miles to the east—the Rio Grande and 300 miles to the west—the lower Colorado River. Without the perennial flow of the San Pedro River, the old native forests and grasslands are desiccating and dying. As the vegetative habitat withers, the animal life—from the leopard frog and longfin dace to the gray hawk and green kingfisher to the nectar bats and ghosty neotropical cats, are essentially homeless and their cupboard is bare.

The legal battle to establish water rights for the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area is essential. But the adjudication is mired by lawyers, at the behest of politicians and developers, who scrutinize and protest literally every sentence, every table and graph, every piece of evidence that the BLM has collected and presented, establishing the numbers which equate to acre-feet of flowing water, vital for the survival of what The Nature Conservancy has called, “One of the last great places on Earth.”

For twelve years, BLM employees and volunteers have walked the entire stretch of the river within the National Conservation Area at the time of the summer solstice—pagan celebration? Not quite. This is the driest time of the year. No matter how much monsoon rain fell the summer before or snowmelt from that winter, this is the time of year when the river and riparian habitat and most stressed. Eight teams of two to six folks—one team at the north end, the longest and driest, of four horseback riders—walk the river bottom with GPS units and notebooks in hand mapping the wet and dry lengths of the San Pedro River. For the past two years similar mapping has been carried out by partners in the rivers’ headwaters in Sonora, Mexico.

The data collected regarding animal sightings and the health of native habitat, notations regarding the intrusion of exotic species, the impacts of human visitation—legal or otherwise—and most especially the extant and changes over time to the perennial reaches of water have contributed to the body of science that is being used to save the river.

This year was different in one very important way. For the first time BLM’ers and volunteers were asked to record their deeper observations as they walked the San Pedro. The teams were asked to spend time during the day—in the SHADE!—quietly sitting alone or with their friends and colleagues, reflecting upon and if they desired, sharing their more personal, emotional, even spiritual, impressions of their relationship to the San Pedro River.

If they were old-timers to the place, they were asked to relate their first impressions of the river. If this was their first time in the area, they were asked to do the same. Comparisons and anecdotes abounded. They were asked to think about and if called to, discuss what they felt about the work they were doing mapping the river, about how they felt about the current situation as the water flows and habitat of the San Pedro River continues to decline in volume and health. They were asked if they had hope. Naturally, as most of the BLM employees and volunteers are or were professional scientists, talking about intangibles was difficult for some, even irrelevant. But others opened up and proved poignant and eloquent in their thoughts and speech—some surprising even themselves with the passion with which they spoke. Anger at the overt perpetrators was outed and covert actions proposed and then let go. Deep sadness was expressed. Guilt at being a human being and a contributor to the demise of an entire ecosystem was quietly born by the honest.

Yet, for all the somber reality of hiking a great simple river during her driest days, joy and refreshment and wonder at the rare beauty of this desert river were the largess of the day. For these human beings who have not given up hope, but continue to explore the San Pedro River and document, even if only in their hearts, what they see and smell, and hear and touch, and FEEL, was time very well spent. They will be there next year. They will be there for as long as they are needed. Until the San Pedro River flows with continuous wild abandon, as a river should.

San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area

RECENT STORIES

For the Gulf Coast

Our beaches are being bombarded almost daily since the end of the first week of the sinking of the Deep Water Horizon with gatherings of people or all stripes: protests, prayer groups, volunteers, rallies for [...]

Remembrance Day for Lost Species in Helsinki 2023

On November 30th, there was first a session organized by the Finnish social and health sector project about eco-anxiety and eco-emotions (www.ymparistoahdistus.fi). This “morning coffee roundtable”, a hybrid event, focused this time on ecological grief [...]

Ashdown Forest

Ashdown Forest is an area of natural beauty in West Sussex, England. It is also one of the very few remaining areas of extensive lowland heath left in Europe. This rare and threatened landscape is [...]